Nothing compares to those thankfully sparse moments in life when you are utterly screwed. I’m not talking about the anxiety that burns all over like shingles when you see a Highway Patrolman with a speed gun and you’ve had a couple beers. I’m talking about the mind-numbing, strangely Zen-like, clear-headed calmness of being totally, completely screwed.

Here I am looking at another shitty bus, as I stand outside of it. Nothing looks wrong with it, I just know it won’t move. Maybe its tire blew…..maybe it ran out of gas….who knows? All I know is I’m on a road somewhere outside of Asuncion, Paraguay and the sun is setting. Up the road, I see jungle. Down the road, I see jungle. I wouldn’t even be able to retrace my steps because navigating the vast concentric rings of run-down tool stores surrounding the capital (store is giving them way too much credit—more like hastily erected cinderblock market stalls) would be like that nightmare where you keep walking but never get anywhere and everything looks the same.

“So what are we gonna do, Pedro?” asks this guy in Spanish. All I can choke out past the rock of despair weighing down my stomach is, “I…don’t know.” This guy was not someone I wanted to talk to. For one, I’m tired, hungry, and dehydrated. AKA I’m irritated. I spent all night on a plane flying over Brazil on New Year’s Eve (cheaper flight), and in anticipation of a 4 hour bus ride with no stops, I have barely eaten or drank water, for fear that I would have to pee and knowing there would be no stops.

I could go on for hours about the inhumanity of buses in foreign countries, but that’s for another day.

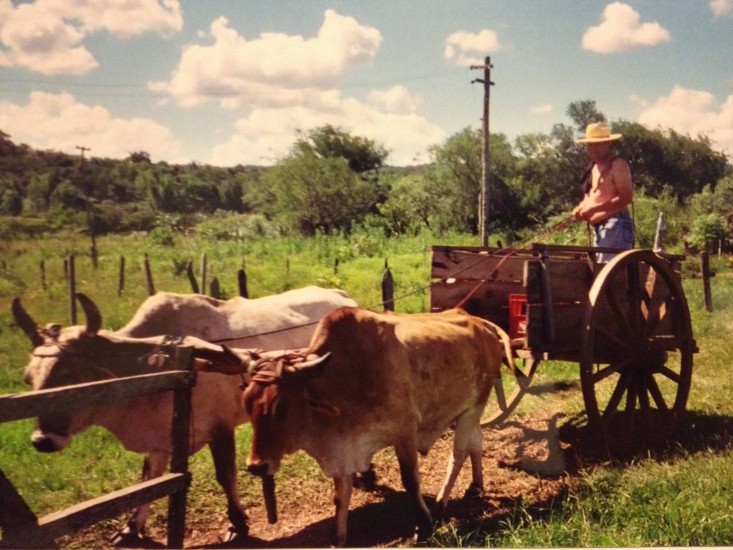

Although this is the alternative

To make matters worse, for six hours, not a single bus came, the heat of a Southern Hemisphere January is singeing my skin, and wringing out the last drops of moisture my cells are retaining, and this same guy sat near me in the bus station the whole time, striking up awkward conversation and asking a lot of questions. Inquisitions by locals in any foreign country are unnerving, but to top it off, this guy was missing enough teeth to be on a strictly liquid diet, and he definitely looks like he’s not all there in the head.

“I tell you what. My dad lives a bus ride away from here,” he says. “You can come over, have dinner, stay the night, and we will catch a bus in the morning.” Great. Code Red, Code Red! All the little men manning the NORAD anti-ballistic missile base deep within my cerebral cortex are furiously pulling levers and pushing buttons, under the grim flashing of the crimson warning lights. Then the nuke hits, annihilating the base. It had to….because I said, “OK.”

I throw on my backpack, morbidly contemplating how many pieces this guy is going to have to cut me up into to fit me in an oven, or pot, or a freaking frying pan, oh God, I didn’t realize how many sadistic ways there were to eat a human being before this! My only consolation as we trudge on is that there should be at least some people around as we go. That, and the decision that if so much as a tree branch snaps, I’m bolting, and getting the fuck out of Dodge.

It’s night by the time we get on a bus that looks like a death trap. If I’m not gonna be stuck in a hole in this guy’s basement, putting lotion on my skin, I’m gonna die in a fiery inferno the minute this bus hits a pothole. We go in back, and I sit down. The cumbia music bleeding out of the open windows into the dark, humid night is at least somewhat calming. On top of that, I’ve been listening to this old drunk next to me drone on in Guarani, exhaling stale liquor and tobacco-laced puffs of Paraguay’s native language all over my cheek. I only know one word, and I’m answering him with it at every pause: “Hê”— “yes”. At least if I make friends with this old man, whose twenty-something son is propping his drunk-ass up, there’s some possibility they would start swinging on Ted Bundy over to my right the minute I sound the alarm.

Is this thing leaking fuel? If someone even lights a cigarette, this shit is over

Our stop comes, and it’s just me and Jeffrey Dahmer, walking down a street that doesn’t have much light. My hands are white-knuckling my backpack straps, my leg muscles are tense, and I’m scouting out which house has people in it, which house I can run to the second his molesty hands pass the event horizon of my personal space bubble. We get to one house, and he says, “This is it.” Yup, this was it….the place where my bones would be ground to dust, fertilizing the palm trees, a place my mom would never know, never know that the carbon and sodium atoms that once came together to make her son now blended with the famously crimson Paraguayan dirt in a non-descript front yard.

The gate squeaks open, and I walk in. I hear noises, voices, a TV blasting, and Jeffrey says one sentence in Guarani.

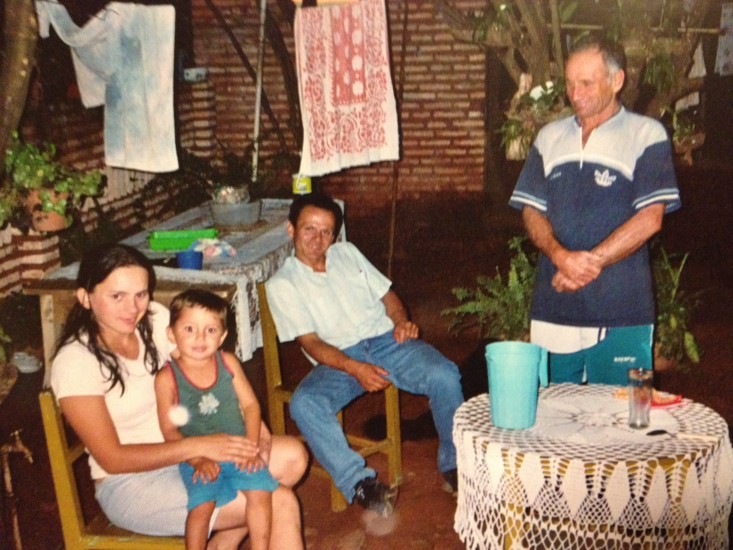

Suddenly the people in the yard erupt into beaming smiles! The most non-threatening old man comes up and shakes my hand vigorously. A young woman, resembling Christina Ricci with a snaggletooth and strangely-attractive, sits me down on a chair in the yard, while a little boy, her son, runs around shirtless in flip-flops playing with his new toy, a broken branch. Food is laid out in front of me: delicious grilled beef, rice, half of a lemon to squeeze on top, and fruit salad served with its juice in a pint glass. The faded colors of their clothes, probably sent down from charities in America, jumble together in front of my eyes in the faint light, the noise, and all the commotion.

Jeffrey’s in the middle….still looking pretty creepy…

People are talking to me, but I am catatonic, experiencing the ethereal, pleasureable effects of buttloads of adrenaline slowly ebbing out of my veins, as my knees buckle with relief. Good I’m already sitting down.

The young boy, probably 3 years old, doesn’t understand what we are saying in Spanish because he hasn’t been to school yet, and his linguistic reality is still the ancient, pre-Columbian words that named the surrounding creeks and hills eons before a Spaniard or his horse ever treaded over them. He’s definitely proud of one thing: he can pee like a big boy and does it all over the yard like a dog marking its territory, unfazed by the mortified scolding of his mom.

When it comes to time to sleep, I’m let into the only room of the house. It has 3 beds all made, and a halogen lamp that usually would make a room feel sterile and cold like a hospital. Yet with the calming blue of the paint on the walls, the room actually glows. Feels like home. I start laying my things next to one of the beds, and behind my back, I hear a hesitant, and almost bashful “Buenas noches…” from the young woman, as she starts to leave. She has been averting her gaze all night, and the prospect of being alone in a room with a man with green eyes, unimpressive in the United States but syrupy twin seductors here, is probably what’s bothering her.

I say, “Wait! Where are you guys going to sleep?” She spins nervously on her heels, posture hunched and eyes still down, “We just got a new fan, and it’s noisy. We can’t sleep with it on. But you’re from America, and you’re used to noise, so you will sleep with it just fine. We will sleep outside.” And just like that, she was gone, leaving me stupefied at this pathetic excuse for one of the most heartwarming gestures I’ve ever experienced.

The house doesn’t look so scary in the daylight

The next morning, we all wake up, have breakfast, and Jeffrey and I set out into an early morning sun that’s already baking bricks out of the cracked red dirt. And now we were sitting in the same bus terminal in downtown Asuncion, my emotions completely opposite the suspicion and terror I had felt about Jeffrey the day before. Yea, he was missing teeth and he looked like he got dropped on his head as a baby, but I was proud to sit next to him.

The bus terminal

At some point I rifled through my things and pulled out a crisp $20 bill. Not a lot, but I was broke and that money will buy a week’s worth of groceries in Paraguay. I handed it to him, he refused, and I said, “Take it. You have no idea, but you saved my life.”

Waiting for the bus

With some more polite arguing and refusals, he pocketed it. The bus came, and we set out again, passing miles and miles of herramienta stands and corrugated metal roofs, sucking in big gulps of car exhaust and the acrid smell of burning trash through the open windows. Ahhh, the unforgettable (and amazingly agreeable) smell of South America.

About 2 hours into the ride, Jeffrey stands up, and says, “Goodbye, Pedro.” My heart was engorged with emotion, and his handshake felt far too brief. I promised him I will find a way to send his family the few pictures I snapped at their house, and then I watched his back as he jauntily strutted down the aisle of the bus, clearly self-assured that all the women of the bus were swooning over his toothless grin.

Lesson learned: It’s scary out there, but the whole world is not evil. People will be strangely and effusively kind to you for nothing in return.

-Peter, 32, (Tempe, Arizona), former Peace Corps volunteer in Paraguay